Road trip into

“The land of liquid gold”

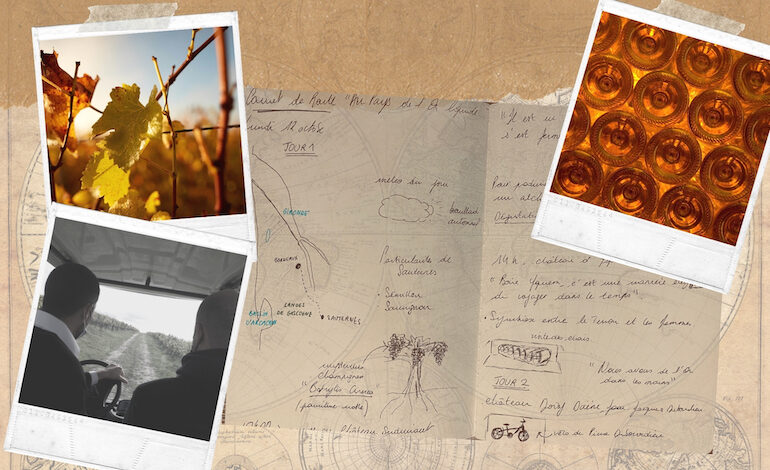

Sauternes is a truly unique appellation. You need to see it to believe it. As ardent wine-lovers and adventure-seekers, we set off during the harvest season to meet some of the women and men who help this liquid gold to shine. Here is what happened on that magical trip.

DAY 1

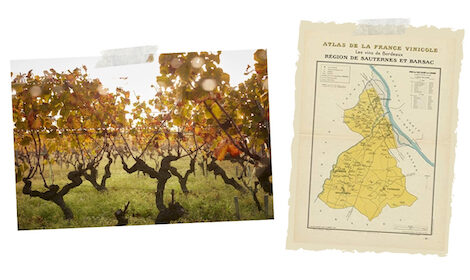

There are many ways to celebrate good news. But setting off on a trip is probably the best. When my best friend Antoine announced that he was going to become a dad, we decided to set off on the trail of a truly unique wine. The adventure began on Monday 12 October. The sky was blue, and the sun was just starting to warm up Place Pey-Berland. It was 8 in the morning, and it looked like we had a fine Autumn day ahead of us in Bordeaux. These were perfect conditions in which to explore the side roads of the Gironde – just as well, since for the next two days we would be winding our way from château to château in Sauternes and Barsac. Along the way, we would be meeting the master craftsmen who make the world’s most famous sweet white wine. This was to be a voyage of discovery into the heart of an appellation where Sémillon and Sauvignon Blanc are transformed by a mysterious fungus to produce a one-of-a-kind golden nectar.

But by the time we hit the “Deux Mers” motorway, the weather was changing. The morning sunshine was replaced by much more autumnal conditions. Twenty kilometres out of Bordeaux, a thick fog descended on the road. Visibility was down to ten metres maximum, and we could barely make out the towering pines which mark the beginning of the vast Landes forest. This might have seemed like a pretty lousy welcome from the local weather gods. Not at all! In fact, we couldn’t have wished for better conditions for our trip to Sauternes! Here we were, face-to-face with the legendary autumn fog. This is what happens when the cool waters of the Ciron collide with the warmer waters of the Garonne. The humidity provided by this fog creates the right conditions for a certain little mushroom to develop – a fungus eagerly awaited by the winemakers of Sauternes and Barsac. This magical fungus bears a suitably evocative name: Botrytis cinerea. In just the right conditions, this is the source of the famous “noble rot”. It takes hold of the grapes, transforming the fruit. The berries become condensed and concentrated, their pulp packed with sugar and aromatic potential. This is what gives Sauternes wines their grandeur and complexity.

The Sauternes microclimate

Just after 10 O’clock we rolled down a broad driveway, flanked by vines, to arrive at Château Suduiraut, a Premier Cru in the 1855 classification. We had been promised gently undulating hills, with vines decked out in the orange-hued finery of autumn. To be honest, we couldn’t see a thing. Sitting at 50 metres above sea level in the village of Preignac, Suduiraut’s history stretches back for centuries. The château’s 92 hectares of vines are spread across the limestone soil of the Barsac plateau – which gives the wine its lively acidity and freshness – and the clay-sand gravel of the Sauternes hills, which provides power and richness. Pierre Montegut is the man responsible for making the most of this wonderful terroir. Despite the weather, which was at first glance conducive to the development of Botrytis, the Technical Director looking somewhat preoccupied. He had been hoping to harvest today, but was forced to accept that the conditions were just too damp: “The Sauternes microclimate is all about foggy mornings, followed by warm and windy afternoons. The problem right now is that we have the fog, but we don’t have the sun!” For the last 3 weeks it had been raining steadily in the south of the Gironde. Here, as in much of France, the warm, dry summer had given way to a rainy autumn suddenly and without warning. The thermometer was struggling to get above 15 degrees. When the harvest started in mid-September, this looked like a vintage which would be defined by its radiant sunshine – but now, the fate of the harvest seemed less certain. Too much moisture could compromise whole vines, a nightmare scenario for the winegrowers. Their biggest fear is the arch-nemesis of noble rot: grey rot. Bunches affected by this rival fungus are unusable, and need to be cut from the vines and abandoned. Pierre Montegut seemed resigned to his fate: “We’re not in control of much around here”, he laughed.

Barely fifteen minutes into my visit to Sauternes, I had been hit by one of the region’s fundamental truths. The fact that Sauternes exists at all is something of a miracle. Producing this liquid gold requires a goldsmith’s touch, an alchemist’s flair and a good dose of philosophical perspective. The ability to give your all, knowing that certain things are beyond your control. To accept the changes in the weather and prove your resilience. The patience to wait as the fungus works its magic. Sometimes it happens in early September, sometimes in late November. Botrytis cinerea has a mind of its own. One vine might be covered in it, while the next vine is untouched. Pierre Montegut let us taste a grape transformed by noble rot: “this grape has reached the ideal level of noble rot, but the next bunch along isn’t ready yet”. To achieve true excellence, the grapes need to be picked one-by-one and the harvest period stretched over several weeks, with between 3 and 6 passes depending on the vintage. Only then can the winemaking process begin.

Saffron, roast pineapple and a moody teenager

At Pierre Montegut’s invitation, we set off to taste the fruit of his team’s labours. In the tasting room, he introduced us to the immense aromatic richness of his wine. As enthusiastic novices, but novices nonetheless, over the course of that tasting session we were amazed to discover notes of tropical fruit, honey, cinnamon, saffron, mint and even roast pineapple. The aromatic palette of Sauternes is like a vast sensory playground, with as many as 100 aromas to explore. The 2016 vintage proved to be slightly less expressive, not yet willing to reveal its full potential. Pierre Montegut was not worried: “Right now this vintage is in its moody teenager phase, it’s a closed book. It will begin to open up in two to three years”. Needless to say, my own moody adolescence was a lot more dramatic than the current state of this charming wine.

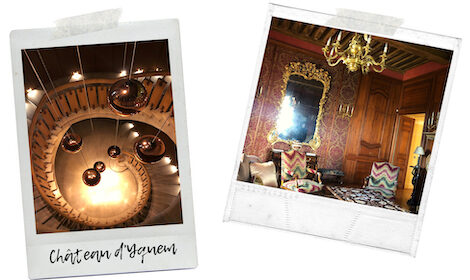

After a nice lunch at Le Saprien, in the heart of the picturesque village of Sauternes, we had an appointment with a legend. The sun had made an appearance, and was shining down on Château d’Yquem. Pierre Lurton himself was waiting to show us around. From the crest of the hill, 90 metres above sea level, the view across the whole appellation is breathtaking. The medieval castle, with its four towers corresponding to the points of the compass, looks out proudly over Sauternes. In the shadow of this holy mountain, one hundred hectares of vines cascade down a gentle slope to the banks of the Garonne. Here, there is the enduring sense of being at the heart of a hard-won legend. At Yquem, as elsewhere, man is at the mercy of the weather: “This is not Roland Garros, we can’t roll out the roof”, Pierre Lurton joked, before adding on a more serious note, “to make this wine, you need to achieve a perfect symbiosis between man and terroir. And then a perfectly imprecise variable comes into play: the weather. Here at Yquem, when man draws on his expertise and succeeds in overcoming the odds, the result is sublime. We can search far and wide but, at the end of the day, Yquem all comes down to risk. If nature is not on our side, and if we don’t achieve the requisite level of excellence, we decide not to produce the vintage.” At Château d’Yquem, they call it the 20-year curse. In 1952, 72, 92, and 2012, no Sauternes was made here. “If anyone offers you a bottle from one of those years, it’s a fake!”, Pierre Lurton warns us.

On the afternoon of our visit, the clement conditions meant that picking was in progress. In all four corners of the estate, far off amid the vines, we could just make out the heads of a handful of pickers poring over the precious fruit. This scene echoed throughout the appellation. The morning’s fears had evaporated, and a sense of enthusiasm had returned. Taking advantage of the break in the weather, the seasonal workers were busy. Their vans dotted the side of the road, as they set to work in the vineyards at last. In the courtyard at Yquem, the grapes were coming in ready for pressing. Wisps of grey smoke, released by the botrytised grapes, rose up from the trailers laden with golden fruit. After a tour of the cellars, where the 2019 vintage is still slowly ageing in its oak barrels, it was time for us to ascend the magnificent staircase which leads to the holy grail: the tasting room.

A trip back in time

As François Mauriac once wrote: “the summers of yesteryear still burn brightly in each bottle of Yquem”. Pierre Lurton once had the privilege of uncorking a bottle from 1810! As he puts it: “Drinking Yquem is, in a sense, an elegant journey back in time”. A maxim which made perfect sense as we contemplated our surroundings. Past vintages were lined up against the wall. You could trace the passage of time in the colour of each bottle. As the years pass that vibrant gold becomes gradually darker, making way for amber, mahogany and coffee hues. Close your eyes and you can almost see Thomas Jefferson falling instantly in love with Yquem when he visited the château back in 1787. And there we were, ready to travel back in time, no DeLorean required. Sometimes we can get caught up in the legend associated with a wine, and actually tasting it can be a let-down. Not this time. “Immersing yourself in the light of Yquem” is an overwhelming experience. Even Pierre Lurton, who knows Yquem inside-out, is still stunned by it every day. He whipped out his phone to show us a video he filmed a few days earlier from his car, winding his way through the vines with Chopin on the stereo, as the fog gradually lifted and a blue sky appeared over the château. “There is something magical about this place, a special light which I never get tired of”, he explained. Still floating on a cloud of our own, we left Yquem behind us.

Taking a little time to let the experience settle in, we ventured into a copse on the banks of the Ciron in search of another legendary fungus associated with Bordeaux: the cep mushroom – in vain! We came away empty-handed, and soaked through by another shower. We may not have found any mushrooms, but at least we had managed to work up an appetite. It was time to head over to Lalique, a Michelin-starred restaurant housed in the rarefied surroundings of Château Lafaurie-Peyraguey. The restaurant boasts a magnificent bay window looking out over the vines. The meal was just as sumptuous. Chef Jérôme Schilling is committed to putting the superb Sauternes terroir at the heart of his cuisine, and one dish included the Gironde ceps we had tried and failed to find that afternoon. We decided to play along, matching the dishes with wines from Sauternes. The line-up included a bravura Lafaurie-Peyraguey ‘99 and, more surprisingly, a Switz – a young vintage served over ice with a twist of orange peel. A heresy? “On the contrary, it’s a great idea! It echoes the aromatic profile of a young Sauternes, so it’s certainly not a sacrilege. And it’s a way of introducing Sauternes to a new audience. Serving it like that, in a Michelin-starred restaurant, could really shift people’s perspectives”, explained Jean-Jacques Dubourdieu when we met him the next day at Château Doisy-Daëne…

DAY 2

The love of wine, and Sauternes in particular, runs through Jean-Jacques Dubourdieu’s veins. On the day we met him, his shirt sleeves were splattered with grape must. Just minutes earlier, he had been pumping wines out of the vats at Clos Floridène, a stone’s throw from Barsac. “The Dubourdieus have been winegrowers since 1794. My great-grandfather was a justice of the peace in Barsac. He purchased Doisy Daëne in 1924.” His grandfather Pierre, now 97, still lives at the estate, and has been present for the birth of more than 70 vintages at Doisy. An indefatigable inventor, it was Pierre who created the machine for pulling out stakes. Jean-Jacques’ father Denis, who sadly passed away in 2016, was the founder of the Institute of Vine and Wine Sciences (ISVV). As a consulting oenologist for numerous estates in Bordeaux and around the world, he revolutionised the white winemaking process. Jean-Jacques could hardly choose another path. In fact, he had no intention to: “I grew up in this atmosphere. The vines were my playground, I’d come home from school and make wine. I just don’t feel right when I’m away.” Jean-Jacques was particularly keen to show us one wing of the château. Leaning against the wall was his grandfather’s bike, which he still uses regularly. Inside, we stepped into a somewhat outdated room, austere yet charming in its own way, presided over by a portrait of Pierre Dubourdieu. This is the oldest tasting room in all of Sauternes.

A new bar in Sauternes?

Respect for tradition does not mean rejecting modernity outright. At barely 40 years old, Jean-Jacques Dubourdieu is a member of the new generation taking over in Sauternes and Barsac. A generation which “has known nothing but crisis” and refuses to shrink from the challenges ahead. Commercially speaking, Sauternes has seen better days. For almost 20 years now, this extraordinary wine has been under-appreciated. The appellation has occasionally been labelled as the classic wine “to serve with foie gras at Christmas”, unfairly regarded as too sweet for other occasions. And yet, as we discovered to our delight during this trip, Sauternes is magnificent as an aperitif, served with blue-veined cheese or roast chicken, or even on its own as a dessert, to savour the full extent of its character – as recommended by Pierre Lurton. Tackling old assumptions, Jean-Jacques Dubourdieu, who is currently co-president of the appellation alongside David Bolzan of Lafaurie Peyraguey, is determined to shake things up: “We have gold on our hands. Our history, our classification, our magnificent region, the Ciron river, the Landes forest: the biggest challenge for us is to get people to come and see it for themselves.”

There has surely never been a better time to visit Sauternes. A fresh breeze is blowing through the appellation. Reinvention is in the air. Everywhere you look, exciting initiatives are springing up. At Château Rayne Vigneau you can enjoy a tasting session atop a hundred-year-old cedar tree, gazing out glass in hand over the picturesque Sauternes landscape. Château Climens, meanwhile, is pioneering a slow tasting movement complete with yoga and meditation sessions: “Things are moving in the right direction, we need to create experiences which go above and beyond wine. With David Bolzan, that’s the motto we’ve set ourselves. We’d love to create a wine tourism centre focused on sweet wines and noble rot. We have so many great stories to tell.” Before bidding us farewell, Jean-Jacques Dubourdieu shared one of his dreams for the future with us: to open a wine bar in Sauternes. We promised, hand on heart, to be there for the opening night.

After yet another fascinating encounter, it was time for us to hit the roads of Sauternes and Barsac again. In barely 36 hours, we had already become deeply attached to the region and its rustic, peaceful, almost timeless atmosphere. The winegrowers of Sauternes share an admirable sense of resilience, and the humility of those who know that, without nature, they are nothing. Enchanted by the special spirit of the place, we found ourselves marvelling at the estates dotted throughout the rolling landscape, and, of course, the omnipresent magnolias which adorn the façades of the houses. With the sun once again shining down on us, the green vines were beginning to take on a golden hue, with hints of amber in places.

Hogwart’s amid the vines

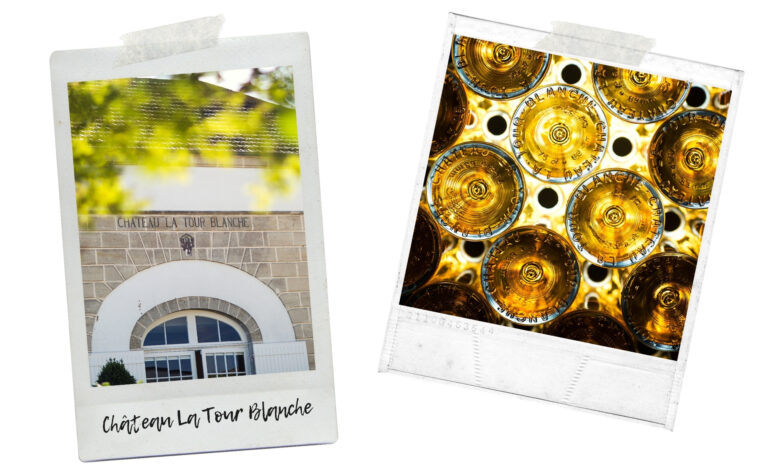

Before heading home, there was one last stopover on our itinerary. Up on the hills of Bommes, we had an appointment at a very unusual château. In front of the estate, a rugby pitch surrounded by an athletics track seemed bizarrely out of place. A few metres on, we were surprised to come across a concrete handball court. Welcome to La Tour Blanche! While it may look like an athletic high school from the outside, it is in fact a Sauternes Grand Cru Classé…which also happens to house an agricultural high school. La Tour Blanche is one-of-a-kind. It serves as a sort of Hogwart’s amid the vines for apprentice alchemists. Between these walls, the art of winegrowing and oenology have been passed down since 1909. A project dreamed up by Daniel Iflla, a rich patron with a faint hint of megalomania and a nickname to go with it – Osiris. He purchased the château in 1876, and after his death the French government converted it into an agricultural high school. There are currently 150 pupils enrolled here, learning the delicate art of winegrowing.

Miguel Aguirre is the château’s estate manager. Originally hailing from Colombia, but having spent some of his formative years in Châteauneuf du Pape, Miguel has retained a Provençal accent which comes as a surprise here in Bordeaux. He arrived at La Tour Blanche in 2016 and immediately fell under the spell of Sauternes. Smiling broadly, he invited us to hop aboard his golf cart to explore the estate. The wheels soon began to sink into the mud, as we trundled on slowly before coming to a halt in the middle of the vines. We clambered up the watchtower which stands guard over the estate. The view was spectacular, and a pleasant breeze greeted us at the top. A blessing for the winemakers: “We need more sun and wind over the next few days. This time of year is very stressful for us, we could lose almost a whole year’s work on one roll of the dice”, Miguel admitted. This serves as further confirmation that here, more than anywhere, winemaking is a calling. Like Jean-Jacques Dubourdieu, Miguel Aguirre wants to hear more people talking about Sauternes, sharing in the grandeur of this appellation “as demanding as it is irresistible”. Last summer, Miguel and his team set up a pop-up bar amid the vines of La Tour Blanche, inviting musicians and organising a “golden aperitif” party, providing an excellent introduction to this wonderful wine.

It was almost time for us to leave. Amid the bucolic surroundings of Château la Tour Blanche, we chatted about football, winemaking, fatherhood and friendship, about the beautiful region of Sauternes and Colombia. With a heavy heart, we steeled ourselves for the return journey to Paris. To mark the end of our adventure, Miguel uncorked a bottle of 2005, a sun-kissed vintage to round off our trip in style. I thought of the commitment, the passion, the unpredictable struggle with the elements waged by the men and women of Sauternes to create a wine of such purity. After one last sip of liquid gold, one thing was certain. We’ll be coming back to Sauternes.

A.J, wine lover and journalist